Alan Jacobi, who has died of cancer aged 67, transformed the entertainment industry by bringing a spectacular new dimension to performance, whether on stage, in stadiums, or on city streets. AJ, as he was known, revolutionised the way theatre works, his company Unusual Rigging flying people, scenery and effects with apparent ease by using sophisticated backstage solutions.

A self-taught engineer, AJ virtually created the rigging industry out of a background in theatre lighting. When he began, in the early 1980s, technicians still hung their own lights, but in the era of extravagant musicals, rock concerts and spectaculars AJ saw an opportunity within the gravity-defying ambitions of designers and directors.

The flying mechanism for the dazzling 680kg chandelier in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera that flies out into the auditorium before plummeting down above the heads of the audience at a terrifying three metres per second – that is AJ’s creation. The descending helicopter in Miss Saigon; the moving scenery in Les Misérables; the flight of Mary Poppins into the gods – his fingerprints are all over these moments of theatrical magic.

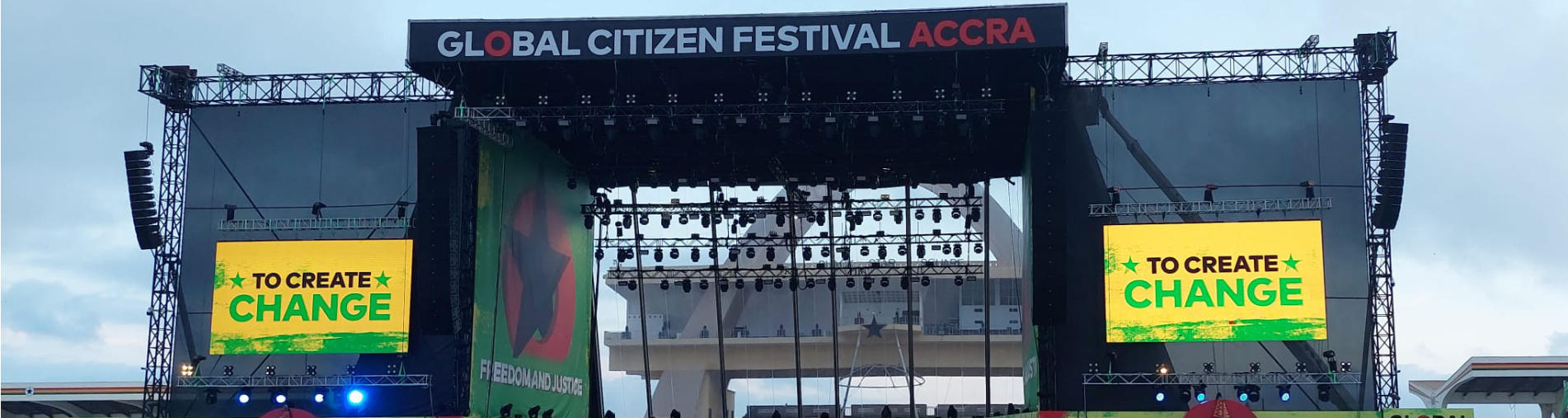

Alan Jacobi in Piccadilly Circus, London, where he created an actual circus, including ‘angels’ on zip wires, for the 2012 Olympics celebrations. Photograph: Matthew Andrews

He was also a producer of national ceremonial events. Appointed to run the Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2002, over one weekend he oversaw military and civilian parades, the first concert in Buckingham Palace gardens, a firework display using 2.5 tonnes of pyrotechnics shooting 800ft into the air, a fly-past of 27 aircraft including Concorde and the Red Arrows and the laying of 500 miles of cable for all the technology involved.

Never one to accept constraints, AJ gave the capital some of its most memorable events. I first worked with AJ in my role leading the cultural work for London’s City Hall, when he masterminded Royal de Luxe’s astonishing Sultan’s Elephant, a giant mechanical elephant who took up residence in central London for four days in 2006.

When we had the bright idea of closing Piccadilly Circus for the first time since VE day to create an actual circus for the 2012 Olympics, I knew there was only one person who could make it happen. Thousands of people flooded the streets and watched angels on zip wires traverse across the sky from building to building dropping 1.5 tonnes of feathers from the air. For much of the sporting spectacle anything that flew or moved through the air only did so by his design: TV cameras, equipment, flags, even people – most memorably the arrival of the Paralympic flame in the hands of a disabled paratrooper high above the Olympic stadium.

Another London 2012 commission was with the American choreographer Elizabeth Streb on her One Extraordinary Day. AJ made it possible for the dancers to perform on some of London’s most iconic buildings, most perilously in the spokes of the London Eye.

He handed the streets of London over to artists again with the Lumiere festivals (2016, 2018), in which his considerable invention and sheer bloody-mindedness saw illuminated artworks adorning 50 buildings from King’s Cross to the South Bank.

AJ also lent his expertise to the art world. His portfolio of challenges include hanging Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at Tate Modern (2003), with its giant artificial sun, Fiona Banner’s Harrier and Jaguar at Tate Britain (2010), where the two aircraft were suspended vertically in the Duveen galleries, the installation of enormous suspended latex sheets in Westminster Hall for Jorge Otero-Pailos’s Ethics of Dust (2016), and Antony Gormley’s takeover last year of the galleries of the Royal Academy, where two huge rusty steel apples – one weighing five tonnes and the other two tonnes – were suspended to hover just above the floor in the show’s centrepiece, Body and Fruit.

Born in Southampton, Alan was adopted by devout Catholic parents, Roland Jacobi, a nuclear scientist at Harwell, and Jill (nee Curran), whose faith became fundamental to his own thinking. Educated by Jesuits in Oxford, AJ developed profound convictions around belief, teamwork and loyalty. He left school without qualifications, later saying that the only exam he had ever passed was his driving test. He secured his first job as a lighting assistant aged 16 at Oxford Playhouse, soon moving to the National Theatre at the Old Vic. With his first wage packet he bought a washing machine and, soon after, a symbolic white Jag. So began his lifelong love affair with machinery – fast cars, slow canal boats, tractors and chain hoists.

He worked with Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Peggy Ashcroft and John Gielgud on Tribute to the Lady, the closing performance before the NT’s move to its new site on the South Bank in 1976. There, under Peter Hall, he worked on celebrated shows such as Jumpers and The Oresteia. Refusing to join the backstage strike of 1979, he would saunter through picket lines, arguing and joking with his striking colleagues, rather than evading them by taking the side door. He left the NT soon afterwards, touring the world with theatre shows, music and concert productions. In 1983 he married Peta Harper (nee Seccombe), a model and PA.

The same year he founded Unusual Rigging. The company expanded in 1990 to incorporate the production of large-scale events and five years later masterminded the UK’s 50th anniversary VE and VJ-Day commemorations. Watching him at work, Field Marshal Lord Bramall was heard to remark that if there were ever another war, AJ should be in charge.

A ferocious iconoclast, AJ yet had an unshakeable private faith. As well as being a staunch member of his local Catholic church in Towcester, Northants, he was a founding trustee of Backup – a charity supporting impoverished members of the theatre industry – and ran support groups in his local maximum-security prison. He was passionate about everything he did and loved by all who worked with him.

AJ personally produced major international events for the UK government, as well as weddings for Jordanian royalty. But while he may have counted kings and princes among his friends, he was at his happiest sharing a sausage sandwich with his colleagues in a local greasy spoon.

AJ was made LVO in 2002, following his work on the Golden Jubilee celebrations, and in 2018 received the Gottelier award from his peers in recognition of his leadership of the industry.

He is survived by Peta, his children, Eugenie, Tom and Emma, and five grandchildren.

• Alan Michael Jacobi, rigger, born 9 March 1953; died 13 April 2020

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/may/20/alan-jacobi-obituary

A self-taught engineer, AJ virtually created the rigging industry out of a background in theatre lighting. When he began, in the early 1980s, technicians still hung their own lights, but in the era of extravagant musicals, rock concerts and spectaculars AJ saw an opportunity within the gravity-defying ambitions of designers and directors.

The flying mechanism for the dazzling 680kg chandelier in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera that flies out into the auditorium before plummeting down above the heads of the audience at a terrifying three metres per second – that is AJ’s creation. The descending helicopter in Miss Saigon; the moving scenery in Les Misérables; the flight of Mary Poppins into the gods – his fingerprints are all over these moments of theatrical magic.

Alan Jacobi in Piccadilly Circus, London, where he created an actual circus, including ‘angels’ on zip wires, for the 2012 Olympics celebrations. Photograph: Matthew Andrews

He was also a producer of national ceremonial events. Appointed to run the Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2002, over one weekend he oversaw military and civilian parades, the first concert in Buckingham Palace gardens, a firework display using 2.5 tonnes of pyrotechnics shooting 800ft into the air, a fly-past of 27 aircraft including Concorde and the Red Arrows and the laying of 500 miles of cable for all the technology involved.

Never one to accept constraints, AJ gave the capital some of its most memorable events. I first worked with AJ in my role leading the cultural work for London’s City Hall, when he masterminded Royal de Luxe’s astonishing Sultan’s Elephant, a giant mechanical elephant who took up residence in central London for four days in 2006.

When we had the bright idea of closing Piccadilly Circus for the first time since VE day to create an actual circus for the 2012 Olympics, I knew there was only one person who could make it happen. Thousands of people flooded the streets and watched angels on zip wires traverse across the sky from building to building dropping 1.5 tonnes of feathers from the air. For much of the sporting spectacle anything that flew or moved through the air only did so by his design: TV cameras, equipment, flags, even people – most memorably the arrival of the Paralympic flame in the hands of a disabled paratrooper high above the Olympic stadium.

Another London 2012 commission was with the American choreographer Elizabeth Streb on her One Extraordinary Day. AJ made it possible for the dancers to perform on some of London’s most iconic buildings, most perilously in the spokes of the London Eye.

He handed the streets of London over to artists again with the Lumiere festivals (2016, 2018), in which his considerable invention and sheer bloody-mindedness saw illuminated artworks adorning 50 buildings from King’s Cross to the South Bank.

AJ also lent his expertise to the art world. His portfolio of challenges include hanging Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at Tate Modern (2003), with its giant artificial sun, Fiona Banner’s Harrier and Jaguar at Tate Britain (2010), where the two aircraft were suspended vertically in the Duveen galleries, the installation of enormous suspended latex sheets in Westminster Hall for Jorge Otero-Pailos’s Ethics of Dust (2016), and Antony Gormley’s takeover last year of the galleries of the Royal Academy, where two huge rusty steel apples – one weighing five tonnes and the other two tonnes – were suspended to hover just above the floor in the show’s centrepiece, Body and Fruit.

Born in Southampton, Alan was adopted by devout Catholic parents, Roland Jacobi, a nuclear scientist at Harwell, and Jill (nee Curran), whose faith became fundamental to his own thinking. Educated by Jesuits in Oxford, AJ developed profound convictions around belief, teamwork and loyalty. He left school without qualifications, later saying that the only exam he had ever passed was his driving test. He secured his first job as a lighting assistant aged 16 at Oxford Playhouse, soon moving to the National Theatre at the Old Vic. With his first wage packet he bought a washing machine and, soon after, a symbolic white Jag. So began his lifelong love affair with machinery – fast cars, slow canal boats, tractors and chain hoists.

He worked with Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Peggy Ashcroft and John Gielgud on Tribute to the Lady, the closing performance before the NT’s move to its new site on the South Bank in 1976. There, under Peter Hall, he worked on celebrated shows such as Jumpers and The Oresteia. Refusing to join the backstage strike of 1979, he would saunter through picket lines, arguing and joking with his striking colleagues, rather than evading them by taking the side door. He left the NT soon afterwards, touring the world with theatre shows, music and concert productions. In 1983 he married Peta Harper (nee Seccombe), a model and PA.

The same year he founded Unusual Rigging. The company expanded in 1990 to incorporate the production of large-scale events and five years later masterminded the UK’s 50th anniversary VE and VJ-Day commemorations. Watching him at work, Field Marshal Lord Bramall was heard to remark that if there were ever another war, AJ should be in charge.

A ferocious iconoclast, AJ yet had an unshakeable private faith. As well as being a staunch member of his local Catholic church in Towcester, Northants, he was a founding trustee of Backup – a charity supporting impoverished members of the theatre industry – and ran support groups in his local maximum-security prison. He was passionate about everything he did and loved by all who worked with him.

AJ personally produced major international events for the UK government, as well as weddings for Jordanian royalty. But while he may have counted kings and princes among his friends, he was at his happiest sharing a sausage sandwich with his colleagues in a local greasy spoon.

AJ was made LVO in 2002, following his work on the Golden Jubilee celebrations, and in 2018 received the Gottelier award from his peers in recognition of his leadership of the industry.

He is survived by Peta, his children, Eugenie, Tom and Emma, and five grandchildren.

• Alan Michael Jacobi, rigger, born 9 March 1953; died 13 April 2020

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/may/20/alan-jacobi-obituary

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)